From the NY Times to Netflix: a Brief History of Paywalls

This post was originally published on February 12, 2023.

As a fancy technologist who enjoys looking at celebrity real estate, my three favorite websites are wired, architectural digest, and curbed, and all of them allow me to read a few articles per month before a paywall goes up. Occasionally, I send article links from these sites to my nearest and dearest, and often get the same response: “I can’t see the article, it’s behind a paywall.”

You must be joking me!! I scream internally. College graduation rates are the highest they’ve ever been and no one knows how to get around a paywall. (I’m looking at you, mom.)

That was mean, sorry.

It’s unfair of me to complain that people don’t know how to get around paywalls, when paywalls are so annoying (and expensive) in the first place. I find it crazy that wired.com expects my mom to also buy a subscription to wired.com just to read the articles I send her. I get annoyed whenever I think about paywalls, because they're preventing us from sharing information.

On the other hand, I’m a realist and I know that content can’t be free. Someone has to pay for fun articles, whether it’s readers, advertisers, or benevolent billionaires (oh wait those don’t exist). I’ve watched the tug of war between content creators and paywall evaders for the past ~10 years, and I’ve noticed a few interesting things.

Cookies

First, I should explain what cookies are, and how websites use them for paywalls.

Let’s say you visit wired.com, and wired.com only allows you to view one article per month before you have to sign up for a subscription. So when you visit the site in a Chrome browser, wired.com will add a cookie in that browser saying you visited their site. Next time you visit, tada!, you’ll see a “You’ve hit your monthly limit on free articles, please subscribe now” popup. But – excitingly for those of us who spend way too much time avoiding paywalls – if you visit wired.com in a Chrome Incognito browser, the cookie from your non-Incognito browser won’t carry over, allowing you to view one article anew. (The same will happen if you switch to Firefox, or to Firefox Private Browser, or to Internet Explorer, and so on and so forth.) There’s also a somewhat harder solution, which is to delete the cookies manually in the “inspect” page of any browser:

There are also other, more complicated, workarounds for avoiding cookie-based paywalls, like using the Wayback Time Machine, or the Reader Mode browser extension, or others that you can find online.

Paywall History Exhibit A: The New York Times

Remember 2011, when you could delete everything after the “&gwh” in a nytimes.com url, and the paywall would just disappear? Those were the good days.

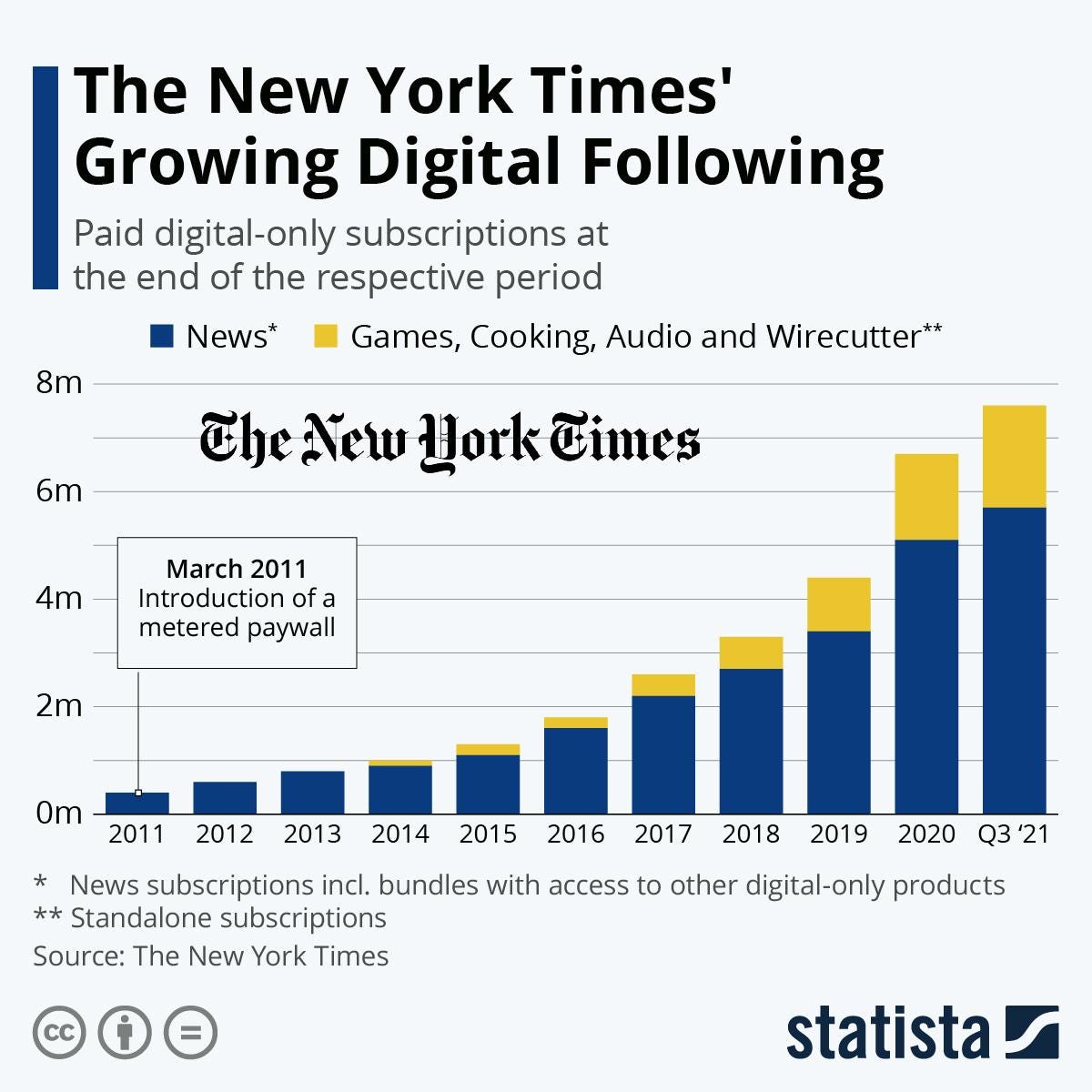

By now, the New York Times has caught on to my — and everyone else’s — paywall evasion schemes, so as of 2019, they’ve stopped allowing ANY free visits to their site. You visit, you subscribe, you read. So in late 2019, I grudgingly signed up for a digital subscription to the Times. And so did the rest of the world.

In the first half of 2020 alone, the Times added one million users:

I’d bet that The Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, and everyone else are likely to copy the no-free-articles system in the next few years (unfortunately for me).

If cookies weren’t Big Brother enough for you, don’t worry, there’s always IP addresses

Okay cool, so we’ve seen how companies can work around the cookies-don’t-really-work problem.

Streaming services have a slightly different problem. They’ve already done what the Times has done, requiring you to subscribe before you can view their content. But human beings are conniving things, and they quickly figured out a low-tech way to get around having to pay: password sharing.

I’m sure the Times has suffered from lots of password sharing over the years, but they don’t have the hundreds-of-millions-of-dollars in engineering resources to address it. Netflix, on the other hand, has an unlimited R&D budget, and they recently caught on to how much money they’re losing to password sharing, saying in their 2022 Q1 that “In addition to our 222m paying households, we estimate that Netflix is being shared with over 100m additional households.” 100 million households is a lot of lost money; if we assume that Netflix makes around $11 per customer, that means they’re losing out on $1.1 billion per month.

So Netflix decided to crack down on password sharing, and they decided to do it using the concept of "households". Households cannot share accounts, and by their definition, one IP address constitutes a “household.”

Just last month, Netflix added a footnote to their subscription plan page that explains “Only people who live with you may use your account.”

Too lazy to fake my IP address

Now, it should be stated that it’s possible to fake your IP – one popular option is to use a VPN, for example –but Netflix has started cracking down on VPNs, and I'm too lazy to play cat and mouse with Netflix, especially when their cheapest subscription is only $6.99/month. Cheaper than Hulu and HBOMax!

So once again, I’ve given up on playing cat and mouse with large corporations who want me to upgrade from their freemium plan.

In conclusion

Why do we live in a world where it's impossible to share content online? Why can’t my Times subscription allow me access to the Post, or my Netflix subscription allow me to watch a few episodes of HBO Max? Instead, internet content has only bifurcated over time, with TV companies creating their own online subscription services to compete with Netflix, and more and more news websites adding paywalls of their own. In the pre-internet age, we had to share articles by clipping them and sending them via snail mail; it feels like with all the technological innovation we’ve seen in the past decade, we’re right back where we were in the first place.

FAQ

What are the ethical implications of using methods like cookie deletion or IP address manipulation to bypass paywalls?

Ethical implications of circumventing paywalls involve considerations of fairness and sustainability in content creation. While it may seem innocuous to delete cookies or use VPNs to access free content, these actions undermine the financial model that supports journalism and creative industries. Content creators rely on subscriptions and ad revenue to fund their work, and bypassing paywalls reduces their ability to sustain quality journalism and entertainment. Moreover, such actions may violate terms of service agreements, potentially leading to legal consequences. Therefore, while frustrations with paywalls are understandable, ethical users often opt to support content creators through legitimate subscriptions or other authorized means.1

How do paywall strategies differ between different types of content providers, such as news websites versus streaming services like Netflix?

Paywall strategies vary significantly between news websites and streaming services like Netflix, reflecting the distinct nature of their content and revenue models. News outlets often employ metered paywalls, allowing limited free access before requiring a subscription. This approach aims to balance audience reach with revenue generation from dedicated readers. In contrast, streaming services typically offer no free content, relying solely on subscriptions for access. Strategies also differ in how they combat password sharing; while Netflix restricts account sharing based on IP addresses, news sites face different challenges with user authentication. These differences highlight how paywall strategies are tailored to the specific needs and dynamics of each industry.2

What are the broader implications of the trend towards exclusive content and paywalls on accessibility to information and cultural exchange?

The trend towards exclusive content and paywalls raises concerns about the accessibility and democratization of information and entertainment. As more publishers and platforms adopt paywalls and exclusive content models, access to diverse viewpoints and cultural content may become increasingly restricted based on economic means. This trend could exacerbate digital divides, limiting access to crucial information and cultural exchange among different socioeconomic groups. Moreover, the fragmentation of content across multiple subscription services may lead to consumer frustration and higher costs, potentially reshaping how individuals consume and share digital content. Addressing these broader implications requires balancing the financial sustainability of content creation with ensuring equitable access to information and cultural expression in the digital age.3

This entire section is an SEO experiment I’m running.

See footnote 1.

See footnote 1 (again).